Photo by Jim Witkowski on Unsplash

How do we find balance? We all want balance in our lives, but sometimes we are too busy to notice when we are out of balance. In the space of a breath, creatures around us can offer precious lessons, through metaphors, for what we need to know.

While looking through the window, I watched palm trees get beaten hard by heavy rains, their fronds swaying like a fast wave. I wondered, Why don’t these palm trees fall?

When I was in Maryland, I’d seen large trees uprooted by heavy storms. But a healthy palm tree seldom falls in stormy winds. I’ve learned it’s because palms have pinnately compound leaves—or feather-like fronds. The wind can sway the palms, but it doesn’t knock them down. This is a metaphor for surrender.

I imagined pine trees near the beach or atop the mountains, where the winds are blustery. The structure of pine leaves allows the trees not to resist but to sway—like the palms. But a pine tree’s main structure, with a thick trunk and many branches, becomes a source of resistance to gusts of wind. Over a period of time, a pine tree reacts to the wind with its body, inner structures, and roots, forming a “reaction wood.” This is a mechanical acclimation process through which a tree adjusts its body and growth to new environmental conditions. It’s a form of perseverance.

I try to apply these metaphors for balance to life, and I see many opportunities. Whenever we interact with a stressor over a short or a much longer period of time, our bodies and minds adapt; we find balance.

***

In the spring of 1990, I met my late husband, Patrick, and I began to grow my tree stronger and more resilient; I rebuilt my own core and being with his unconditional love and support. My tree became thicker and taller. We moved to California, and we further strengthened our bonds and love through practicing Buddhist teaching together.

Many challenges—strong winds and storms—fell upon us. But we learned to accept rather than resist; we persevered and built our resilience and our beings’ cores through the hardships. We became just like the pine trees in that we trained ourselves not only to resist but also to accept, which led us to survive and thrive in the most difficult conditions.

Like storms, hardships were the source of our training and learning, which transformed our characters into more centered and grounded. Our trees and roots even became intertwined together, flowering and bearing fruits. After all the hardships, we experienced vibrant souls and spirits within us, our interlaced “reaction woods.”

***

Now I look at us in a much larger picture. Do we humans support balanced lives for other members of the earth’s ecosystems? We’ve observed drastic increases in annual wildfires, the destruction of rainforests, and deforestation in recent years. Shifting barometric pressures have also caused flooding and droughts, leaving wild animals without their natural habitats and dying as a result.

We are at a crucial tipping point of either life or death for many of the earth’s ecosystems.

Humans, animals, plants, and all other organisms are part of the earth’s ecosystems, and we all depend on their services. Food, clean water, climate and disease regulation, spiritual and recreational fulfillment, and life enjoyment depend on the systems and their services. But an ecosystem’s growth and tolerance are not linear. It takes much longer to restore an ecosystem (if it’s even restorable) than it does to damage one. The “reaction woods” theory, perseverance, no longer applies beyond the threshold where destruction begins.

When we lose our sense of inclusivity and become arrogant or ignorant controllers or manipulators of the earth’s ecosystems, we may become destroyers, instead of protectors, of the ecosystems and their resources. When we look back at the Industrial Revolution, deforestation, and other destructions like wars and battles, we can learn painful lessons that show how the ecosystems’ abuses caused crises for and extinctions of other organisms and affected our own survival.

It is, therefore, essential that we do not destroy but rather generate, maintain, and support a good relationship with other members within the earth’s ecosystems. The healthy function of each member in an ecosystem and biodiversity as a whole is the key to integration.

This distorted, rather arrogant view of the ecosystems may come from the widely spread historical “zero-sum” theory. In its principle, no matter how many parties are involved, the sum of the profits remains the same. Therefore, a specific interest group’s profit or abuse results in other parties’ depressed profits, sacrifices, or unfair shares and treatments.

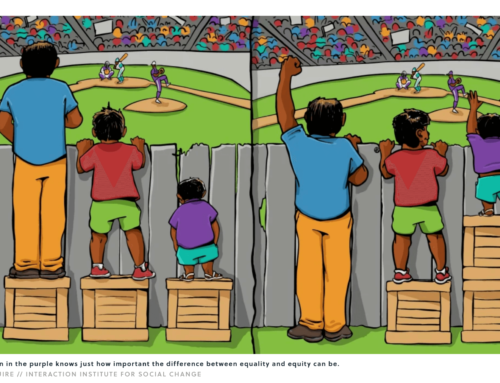

This imbalance in our ecosystems can also explain our societies’ disparities. The recent pandemic has further highlighted our deep-rooted systematic problems. According to the Pew Research Center, the United States has the highest inequality rates among the G7 countries. Our financial recovery from the last recession is disproportionally accumulated in the richest group’s wealth, which has led to further inequality.

Capitalistic exploitation by a few people in our society destroys the ecosystems and their services, and it also causes deep-rooted, long-lasting humanistic inequalities. Economic, social, practical, moral, ethical, psychological, and mental inequalities are widespread. How can we overcome the existing disparities based on this zero-sum attitude? We must turn zero-sum into its alternative: “non-zero-sum” theory.

And Middle Way can help.

Middle Way is one of the principles that Shakyamuni Buddha expounded over 2,500 years ago. He taught his fellow humans to train our potential and achieve wisdom, lovingkindness, and compassion in this very life. But it’s not an ancient philosophy. Practicing Middle Way can bring forth desirable practical outcomes. More importantly, it can transform us to think and act regularly in the true balance based on wisdom and compassion in our daily lives.

Let’s assume individuals or groups represent two or more conflicting ideas. In the zero-sum theory, we vote for the majority, resulting in one winner of the game. Or we average out the shares and then must return favors, depending on the number of shares we have.

Middle Way, however, allows us to experience a paradigm shift from zero-sum to non-zero-sum. It encourages us to nurture the seeds of wisdom and compassion within us daily, at every step of a conflicting encounter. In Middle Way, we can achieve more desirable outcomes, not for one group but all system members; we can all enjoy prosperity and happiness. In Middle Way, the total sum of the outcome increases or multiplies as every member and component increases its potential capacity.

We communicate, listen attentively, understand where each of us comes from, and make efforts to find common ground. It’s not a compromise; it comes from the determination to engage in our goals of collective wealth and betterment. The processes, however, require more time, effort, and resilience because we all must transform ourselves.

In any conflicting situation, Middle Way allows us to better understand our fellow humans and hold on to our sense of integrity and compassion. Based on the fundamental principles of enlightenment, wisdom, lovingkindness, and compassion, we embrace differences. When we agree that we humans and all other creatures coexist and are interconnected and interdependent, it is possible for us to steadily transform ourselves and achieve true balance.

I invite you to this place, together with our fellow humans and other beings, so that we may build our resilience, compassion, and love to live our lives in true balance.

*This article is original and inspired by the philosophies and the tireless works of April Powers (Chief Equity & Inclusion Officer at SCBWI and Global Inclusion, Diversity & Intercultural Strategist) and Heather Mac Ghee (Political Commentator and Strategist, the Author of “The Sum of Us.”)

Leave A Comment