Stopping Opioids Crisis is not an easy task. I’ve posted a series of articles, “How Opioids Affected My Life,” on Illumination. In this last article for the series, I’d like to share my heart-throbbing concerns on the welfare of women and children: how best we can address their health needs in this Opioid Crisis. Please kindly read my previous articles as you may need references from the list.

Opioid Use During Pregnancy

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the number of pregnant women with opioid use at their delivery report increased by 131 % from 2010 to 2017. In the US, about 1 in 5 women with private insurance and about 1 in 4 women enrolled in Medicaid filled at least one opioid prescription in 2017. As imagined, Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) has increased in pregnant women (please see Part Two).

Mental health conditions such as major depressive episodes and anxiety are significantly increased in opioid use and subsequent OUD in women of reproductive ages from 18 to 44 years (1).

During the pregnancy, rapidly stopping the use of opioids is not recommended. It may cause serious consequences such as pre-term labor, fetal distress, or miscarriage. They need to undergo proper medication for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD) or medication-assisted treatment (MAT) by well-trained clinicians under a designated healthcare system. Supervised withdrawal may cause relapses and more returns to OUD.

Neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (NOWS)

When babies are born from opioid use pregnant women, the majority of the babies undergo withdrawal syndrome at their birth. It is called neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), or neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (NOWS) when opioids are the substance of abuse.

According to the CDC, as the number of opioid use pregnant women increased, NAS incidence also increased from 1.5 to 6.6 (4.4 times) per 1,000 live births between 1999 and 2014. In Addition, NAS incidence has significant disparities among the states in 2017; the highest at 56.2 (WV) and the lowest 1.5 (NE) per 1000 live birth.

The onset of NOWS is within one to three days after birth. It lasts one week to 6 months, depending on mothers’ drug abuse history, duration, types of drugs, and combination. The primary symptoms of NOWScome from a lack of regulations of the CNS (central nervous system), particularly with the autonomic nervous system. As babies are born, they keep crying in a high-pitched tone, then exhibit other symptoms like tremors, seizures, fast breathing, fever, sleeping problems, and gastrointestinal system with diarrhea, nausea, vomiting.

Besides acute symptoms of NOWS, babies with NOWS are often born prematurely with a low birth weight of 5 lb 8 oz on average. They exhibit jaundice from premature liver function. They are at high risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).

For treatment, the babies with NOWS are almost always kept separately from their mothers in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and undergo MAT. However, recent studies have shown the effectiveness of “rooming-in,” where mothers and babies are kept in the same room for their sustainable mutual care.

The long-term effect on children with NAS/NOWS is not well established. However, some longitudinal studies showed that children of previous exposure and NAS had significant regulatory problems in their lives: lack of attention, internalized anxiety and depression, externalized aggression. In addition, as part of developmental delay or defects, lack of cognition, learning skills, or motor skills and decreased educational attainment were also reported.

Pregnant women and mothers with opioid use and their Children with NAS

According to Cara O’Connor (2), in the United States, most states have prosecuted pregnant women with opioid use for criminal prenatal drug use with or without child abuse or neglect charges. But many of their high courts have overturned their convictions. On the other hand, states like Tennessee, South Carolina, and Alabama have explicitly permitted these prosecutions, either adding a new statute or including them into the existing ones.

Of the babies born with NAS, 42 % of the cases involve mothers who received substances prescribed for legitimate treatment. But with illicit drug use, opioid use, pregnant women with possible mental conditions are incarcerated once convicted for the charges of illicit drug use and/or child abuse on their fetuses/babies.

In many states, a collaboration between well-trained clinicians and designated healthcare systems is lacking. In correctional facilities in most states, MAT treatment is in serious disparities and not effectively provided, resulting in higher occurrences of continued OUD. As a result, many women who have young children at home lose their custody (2)(3).

Current criminal penalties and state laws can pose a significant barrier for opioid use pregnant and postpartum women to access legitimate care and treatment.

Guttman and colleagues (4) studied on 10-year mortality of mothers of infants with NAS. They analyzed the data from four million women in England and almost one million in Ontario, Canada, for their deliveries of babies from 2002 to 2006. They calculated the death rate up to 2016.

The results have shown that mothers of NAS children died after their births at 11 to 12 times higher mortality risk than babies without NAS. One in 20 women of infants with NAS died within 10 years of after their babies’ deliveries.

Though they collected this data outside the US, possible results in the US could be worse considering disparities and discrimination in our gender, racial, socioeconomic, healthcare, and criminal justice systems. I cannot imagine how much stress both women and children in the Opioid Crisis undergo through various life events even after the deliveries of their babies.

In Conclusion

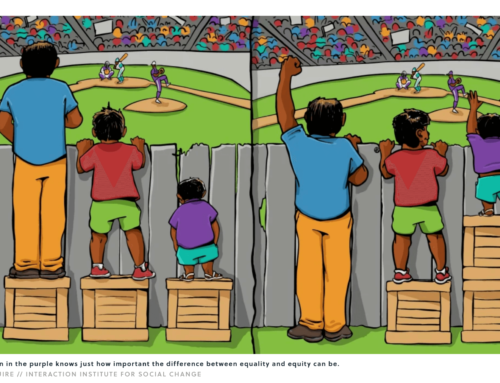

In Opioid Crisis, both women and children are disproportionally affected by the lack of proper federal and state support systems, despite huge budges that have been provided. I hope we can see the current situation with a better understanding to support more effective coordination of the systems.

- 20 to 25 % of pregnant women used opioids at least once during pregnancy in 2017.

- NOWS incidence increased by more than four times from 1999 to 2014.

- NOWS causes newborn babies acute distress and possible long-term problems.

- Pregnant women with opioid use are criminalized in most the states

- Pregnant women with illicit opioid use are prosecuted and often incarcerated.

- A large part of the country does not have proper facilities/clinics to offer MAT,

particularly correctional facilities.

In 2017, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published their policy statement that the ongoing state governments’ prosecutions and punitive approaches provided no proven health benefits for mothers and children, urging more grounded public health responses to the heart of the problems.

References

- Jiani Zhou et al., J Women’s Health. 2019; 28 (8):1068-1076

- Cara O’Connor et al., J Cri. L. & Criminology. 2019; Vol.109 (3): 102-136

- Mary Peeler, et al., J Correct Health Care. 2019; 25(1): 4-14

- Guttman et al., PLoS Med. 2019; 16(11):e1002974.

https://medium.com/illumination/how-opioids-affected-my-life-f03929df2604

https://medium.com/illumination/how-opioids-affected-my-life-6958c72409

https://medium.com/illumination/how-opioids-affected-my-life-c1802ba70e81

Leave A Comment