Opioid Crisis has been one of the major crises in American medical history. Within twenty years since 1999, a half million American died from overdose. 50% of the overdose deaths involve prescription opioids. In the same period, the amount of prescription opioids sold in the US and related overdose deaths have quadrupled. 80% of heroin users were originally users of opioid prescriptions.

Sincere thank you, inspired by my favorite author, Dr. Donna Roberts’ article, I’ve previously published one of my experiences on MEDIUM.

How Opioids Affected My Life- A Personal Story—One

https://medium.com/illumination/how-opioids-affected-my-life-f03929df2604

This time I ‘d like to share my experience with prescription opioids, one of contributors to opioid addiction—Withdrawal Syndrome.

What is Withdrawal Syndrome?

Perhaps most of you’ve heard about Withdrawal Syndrome before. When you abruptly stop the drug(s) or reduce their doses that have been taken in a prolonged period of time (at least for several weeks), it causes variety of symptoms. Examples of such symptoms are runny nose, sneezing, headache, abdominal cramping, gooseflesh, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, pupil dilation, sharp sporadic muscle and joint aches, etc. Before the withdrawal of the drug(s), you have already developed “dependence” to the drug(s). Substances of withdrawal syndrome include alcohol, opioids, benzodiazepines, cocaine, caffeine, nicotine, and cannabis.

Acute withdrawal syndrome lasts days to up to a couple of weeks, however, after the acute phase of syndrome is gone, more than 90% or 75% of recovering opioids users or alcoholics, respectively, develop post-acute withdrawal syndrome (PAWS). Most common symptoms experienced in PAWS are depression and anxiety. PAWS lasts much longer, six months to two years in average. The length of recovery depends on a period of time that the drug(s) are taken, the quantities and the number of the drug(s), and one or more mental illnesses occurring and past medical and psychological history. The longer, the stronger, and the more combined the drugs are used, the severer and the longer withdrawal syndrome would last.

Opioid Use Disorder (OUD), Relapse and Withdrawal Syndrome

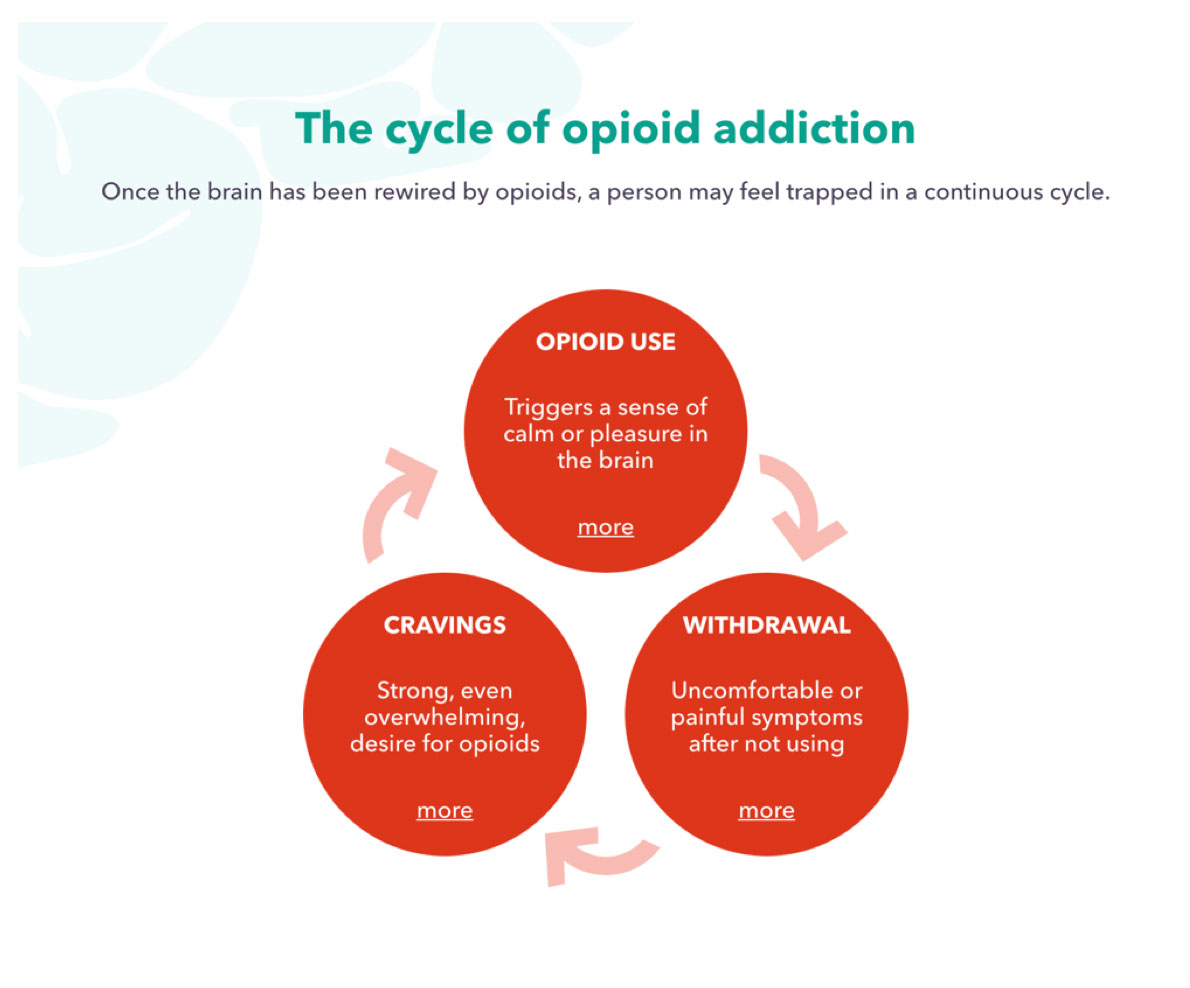

Now we begin to understand the nature of the opioids; how difficult to break its addiction. Opioids addiction is a chronic disease in the brain called Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) despite commonly being misunderstood as a choice or moral problem. Opioids trigger the Reward system (the mesolimbic system), flooding of dopamine and its powerful effect, a sense of calm and pleasure, through this Reward System. OUD changes and rewires the brain to crave rewards. Currently, 8% to 12 % of American prescription users develop OUD.

Developing OUD is the heart of opioids addiction problems, and both relapse and withdrawal syndrome are two largest contributors to OUD. Relapse occurs when a patient, who undergoes withdrawal and the recovery, returns to use the drug. Chances of addiction relapse are very high; as many as 59 % would relapse within the first week of sobriety, 80 % within a month, and 91% would relapse in longer than one month after discharging from a detox program. To prevent overdose deaths and relapse of addiction cycle, patients need treatments. But currently Only 20 % of the OUD patients get treatments and there are serious socioeconomic disparities in the effort.

Image to explain Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) on Rethink Opioid Addiction.com

Withdrawal–My late husband’s case

In June 2013, my late husband, Patrick, suddenly fell ill with severe headache and hydrocephalus. Later he was diagnosed with Stage IV melanoma in the brain, but since Day One of his illness he’d had to use oxycodone (double higher potency of morphine). Later as its dose increased, he was prescribed an additional opioid, methadone (long-lasting with 4 to 10 x higher potency of morphine ), to effectively potentiate its effect yet reduce addiction.

Four days before my late husband Patrick passed away, I visited our local temple in City of Yorba Linda, California for the first time in three and a half years since the last visit. During his illness, we’d given up our continued spiritual pursuit as well as our duties and responsibility as the leaders of the Buddhist teaching. But in the past few months, I’d experienced all kinds of despairs day and night with Patrick, whose brain as the control center of life was severely deteriorated. He couldn’t take medicine latterly either. Finally, I made a decision to return to the temple while his caregiver was watching him. I was at a loss.

Within six hours after I returned from the temple, his condition declined rapidly. He clenched his teeth, and could not open mouth. He couldn’t eat, drink, or even take any medications. I called the hospice immediately. They discontinued all the drugs and began to administer liquid morphine. Morphine was twice to ten times less potent compared to the drugs Patrick had taken. I didn’t know exactly at the time, but this time Patrick clearly began withdrawal syndrome. Despite this problematic situation, a hospice nurse voluntarily left and the health insurance couldn’t replace her with anyone, we were left alone, just the two of us, for the next 24 hours of his critical time.

Starting from the early evening, Patrick moved wildly, writhing in agony. He panted and growled like a wounded animal. He kept tossing, turning and kicking hard with all teeth clenched. At the beginning, I was angry with the fact we were left alone because of the hospice company and the nurse. Not only Patrick, but also I clenched my teeth with tears falling down my cheek. Why are we still suffering from this to the end of his precious life? I wept in agony for a minute.

Then a thought flashed into my being. I knew what was happening. These two events—my temple visit and Patrick’s surrender—were connected. His decaying physical condition had pressed on him long and hard. While he’d fought hard, I knew instinctively that he’d awaited my return to the temple and to make sure I would be back in my faith. My temple visit had allowed him to finally surrender to death.

As I watched him, I had a moment of realization: Patrick would complete his journey with much dignity. He would face whatever came his way, no matter how hard it might become. He would be walking straight up toward death. He’d determined to do so with utmost sincere surrender. Tears in resentment turned to those in gratitude. No matter what came, I would be part of this journey. I was totally grounded and determined to support him through this situation and to the end.

Patrick had suffered from the withdrawal syndrome for one and a half days. I was so grateful that we’d undergone this final challenge together before his passing. Because of the series of struggles before his death had made me believe Patrick was back with me at all the time during this period. After this battle, he became more restful and undergoing a state of serenity and solemnity and ready for the next journey.

Conclusion

From my limited experience with withdrawal syndrome, I imagine how difficult it might be for the patients (and their families) who undergo withdrawal, then possibly would suffer from PAWS for years to come. During a long period of recovery and stabilization, patients undergo challenging depression and anxiety from the PAWS. Without firm yet compassionate hands of families and society, relapse can occur at any time. Disparity in opioid treatment should also be noted for its improvement and further actions.

Leave A Comment