Photo on Shutterstock

Golden Week in Japan ended this past weekend. Every year, pleasant weather in May encourages most families to enjoy this vacation time. However, following the last year, this year’s “Children’s Day” on May 5th, the last holiday of Golden Week, was differed from those held in past years.

Celebrating children’s health, happiness, growth, and development has a long history in Japan. Starting in the eighth century, two of the original five seasonal festivals were dedicated to children—Boy’s Day on May 5th and Girl’s Day on March 3rd. By the seventeenth century, these holidays were commonly celebrated in Japan.

World Children’s Day

According to the United Nations (UN), World Children’s Day was originally established in 1954 as “Universal Children’s Day” on November 20th. On that day in 1959, the UN General Assembly first adopted the Declaration of the Rights of the Child and the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1989.

Each country celebrates World Children’s Day on a different date. In the US, we celebrate National Children’s Day on the second Sunday in June. But what exactly do we aim to achieve on that day in our lives? Is it to make sure children are happy and enjoy that day?

The UN’s webpage describes the holiday’s intent in the following way:

“World Children’s Day offers each of us an inspirational entry-point to advocate, promote and celebrate children’s rights, translating into dialogues and actions that will build a better world for children.”

Reading these words makes me think a lot more about Children’s Day. Children are minors. These statements aren’t given to children, therefore, but to us adults. Rather than share philosophy, what they really do is call for action—for Children’s Day to become everyone’s “entry-point” of inspiration.

These words encourage us to take important steps to build our children’s future. To advocate, promote, and celebrate children’s rights by engaging in practical dialogues and taking concrete actions in our daily lives. If we have any concerns for our children’s future, we must assume responsibility for making it better.

Children in Poverty

Presently, over 700 million people live in extreme poverty (World Bank and UNICEF, 2020). Of that number, 50 percent are children. Globally, one in six children lives in extreme poverty. 45 percent of all child deaths are from causes related to undernutrition (WHO, 2018).

Over two million children—a number that amounts to two-thirds of all deaths from COVID since January 2020—die from severe acute malnutrition each year (UNICEF, 2019). Last year alone, the pandemic forced an additional 150 million children into poverty worldwide. These facts break my heart.

The US is the leading country for international assistance. The amount of foreign aid the US offers fluctuates but usually does not exceed 1% of our federal budget. Over 220 countries receive these funds each year. In 2019, more than a third of the aid was spent on just ten countries, primarily Afghanistan and Israel, to which more than a third of all the aid went toward military assistance.

Aside from military aid, foreign aid from the US is designed to achieve Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in long-term development, humanitarian assistance for life-saving disaster reliefs, treatments of HIV/AIDS, reduction of under-five and maternal mortality, and support for government healthcare systems. This aid has gradually helped the countries who receive it, but the progress is still slow.

According to various national surveys, more than 70 percent of Americans support humanitarian assistance and charity. In 2018, Americans gave more than $427 billion to charitable causes—but only 5% of the total amount went to international causes.

Considering the overall willingness of Americans to give charitably, it seems possible that the government could increase foreign aid to exceed 1 percent of tax revenue, perhaps by building a budget separate from the military assistance. In this way, aid might be distributed more independently and effectively to address poverty worldwide.

American Children’s Welfare

Almost one in every five American children lives in poverty, and the COVID pandemic has exacerbated many existing disparities with race and ethnicity in our society. Children of color are disproportionately affected by poverty and in all other areas of health, education, economics, and legal justice systems. These systemic problems are intertwined with our country’s politics.

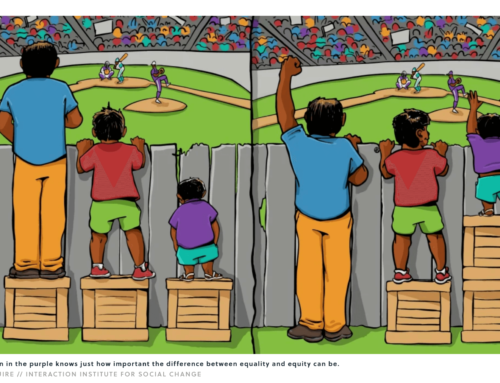

To address this problem, we all know we need to do more than make monetary contributions. If we don’t change ourselves and the system deeply enough, these disparities will persist and worsen.

***

When I browsed around to find the photo I used at the top of this post, I noticed something important: I was looking for a children’s photo with diversity in mind, but I found it quite difficult to find any choices.

Compared to last February, when I was searching for a photo with diversity, this time, I did locate a few more choices. But still, the number of options available wasn’t really satisfactory. There were many photos featuring groups of the same ethnicity/race, but only a few were mixed.

Photo by Nerf Portraits on Unsplash

I don’t have a child, but I saw countless children in my life.

When I lived in Maryland, the hospitals where I completed my residency program for pediatric dentistry and subsequently worked were all located in inner-city Baltimore.

Here in San Diego, where I’ve lived since March 1998, I set up my pediatric dental practice on one of the area’s Native American reservations. I worked until my late husband’s illness ceased me practicing there in the summer of 2013.

I loved seeing my patients and their guardians, often grandmas, mostly Black in Baltimore and indigenous Americans in San Diego.

As I looked into their beautiful, usually dark, eyes, I always sent my love to them. When I was able to change the course of their dental health and their lives, I often felt like crying; I wanted to hold them tight in my arms. And if I knew a kid I was treating was having difficulties at home, I tried to love them even more.

When we don’t know people well or are uncomfortable in a situation, we can get nervous and sometimes afraid. But for the sake of future children, we need to change this knee-jerk reaction. We need to maximize our exposure to all different kinds of people.

Even if you have some resistance to this sort of change, don’t let the children around you repeat your mistakes. We all must be more open-minded and train ourselves to live with DEI— diversity, equity, and inclusion—in mind.

Using TV, books, and other media, and at school and various social activities, we have opportunities for greater exposure to different types of people. We have a long history of segregation in the US; this needs to change. If we don’t make that change now, ourselves, who will be the victims of our ignorance? Our children.

Please join me in this place where we can enjoy all differences together and transform them into the strength that unifies us in One.

Leave A Comment