Photo by Halgatewood.com on Unsplash

Besides the COVID-19 crisis, the Opioid Crisis has been a major crisis in American medical history. Inspired by one of my favorite authors, Dr. Donna Roberts*, I would like to share some stories about my own experiences with prescription opioids.

Today’s News on Prescription Opioids

Between 1999 and 2019, more than 760,000—70,000 in 2019 alone—Americans died from a drug overdose. About one-third of these deaths involved prescription opioids.

According to National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), roughly 26% of prescribed opioids for chronic pain misuse them. Other major sources of opioids for frequent nonmedical users include drugs obtained from friends or relatives for free (26%), drugs bought from friends or relatives (23%), and buying from a drug dealer (15%).

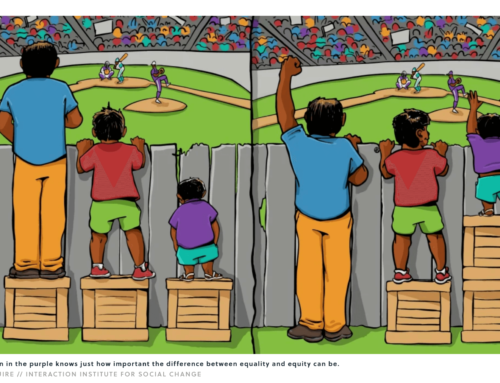

Who Misuses or Deals Prescription Opioids

Misuse of opioids begins with the opioid prescription to a patient. Sometimes the patient gives or sells that drug to someone else, but often they get hooked themselves. In 2019, more than 23,000 people died from the original prescription.

Though Patrick and I were victims of the crime in 2015, we could have passively contributed to a loss of life, and for that, I have many regrets.

***

By the summer of 2015, my late husband, Patrick, had been fighting against his illness with stage IV melanoma in the brain for two years. From day one of his illness until his death, he took prescription opioids all along for his severe headache.

I meticulously organized Patrick’s ever-changing daily drugs, which consisted of more than thirty pills at different times of the day and night. For much of that time, he was taking 60 mg of oxycodone (six 10 mg tablets) throughout the day and 20 mg of methadone—a much more potent and long-lasting opioid than oxycodone—twice a day. If the average person took his daily dose of opioids all at once, they would likely die of an overdose. However, Patrick had become more tolerant of the increased dose of the drugs over time.

Since the onset of his illness up to this point, we’d strictly kept our privacy, according to his wishes. The only people allowed to visit our house were my former cleaning person, Anna, and her family.

Anna had worked in our home for ten years by the time Patrick fell ill in the summer of 2013. She had two daughters and a much younger son. She’d brought them on occasion to our home while she was cleaning, and for the last few years, her daughters had come and helped her clean.

After Patrick suddenly became ill and returned home from his first brain surgery, Anna didn’t want to continue working for us any longer. She was too shocked and spooked by Patrick’s rapid decline to continue. I had no choice but to let her go.

Anna had been having constant problems with her own health, particularly with her weight and with her marriage and family. After she developed back problems in 2011, I’d offered my advice several times. She told me she’d taken opioids—Norco (acetaminophen-hydrocodone, in combination)—for her back pain. As a dentist familiar with the drug, I’d alerted her that she should quit the opioid ASAP and switch to something else—possibly tramadol or even high-dose OTC ibuprofen for a short term. I suggested that she ask her doctor to stop prescribing Norco and instead prescribe her an exercise program and physical therapy.

I wasn’t sure if she took my advice.

***

In May of 2015, just before Patrick’s last hospital and rehabilitation, all of a sudden, Anna contacted me and asked if she could come back to her old job with us. I’d had difficulty hiring anyone for the job and been totally exhausted with Patrick’s ever-critical day-by-day care, so I accepted her back.

By that time, doctors had repeatedly recommended that we switch Patrick’s health care from comprehensive to palliative and perhaps even to the last resort, hospice care.

I was determined to carry through my caregiving for Patrick to the end, so I began to prepare for it. That month, I started remodeling the downstairs with a walk-in shower room and hiring caregivers.

I’d never hired a caregiver before. It turned out hiring caregivers was a tireless work of art and effort. One by one, I’d began to interview potential hires, train them as trials, and then hire and train them more intensively. During the first trial period, Anna’s oldest daughter, Maria, applied for a job with us, and we began a trial with her.

One day during this time period, Patrick had a 911 emergency, went to the hospital, and was admitted for surgery. This was followed by rehabilitation.

I returned from the rehab center one day at the end of May with plans to organize Patrick’s medications in his dispenser for the next month—but when I looked for his oxycodone, I found the bottle with the most recent dispensing date on the label empty. In case I’d mislocated a bottle full of the drugs, I looked everywhere in the chest of drawers that held Patrick’s medicine, but there was no oxycodone to be found.

That morning, I’d left the house key for Anna and Maria to come in to clean the house. Now, the house was tidy, but the oxycodone was gone.

The dispensing of opioids is restricted and regulated. Doctors are not allowed to dispense them casually. And now, the 180 pills that were supposed to be Patrick’s supply for June were gone; he had drugs only for two days in a separate daily organizer.

I had to text the oncologist for another 180 pills, prove my case, and document it with the pharmacy before they finally agreed to replace Patrick’s lost opioids.

I called Anna that day. Both she and Maria said they had no idea what could have happened to the pills. I knew nobody else could have been responsible, but I couldn’t accuse them without evidence. Still, at the end of our conversation, I made sure to say, “I can’t believe the person who stole Patrick’s drugs left no pills in the bottle. Zero. Not even a single pill was there for this person who’s suffering so much. Whoever took them has no mercy in their heart.”

After that day, I carried all the opioids with me every day to the rehab center. But one day, I was carrying so much—four bags of clothes, underwear, toiletries, and food I’d cooked for Patrick—to the center that I didn’t have any room to carry a lunch bag full of the drugs as well. So I hid the bottle of oxycodone in my cosmetics bag and put it deep inside my office closet.

That day, once again, Anna and Maria came to our house while I was gone and cleaned the house.

When I returned home, I went straight to the closet. The cosmetic bag was there, right where I’d hid it. So I took it and opened it.

The bottle was nearly empty—just SIX PILLS left inside.

A bitter taste filled my mouth. I resisted the emotions that were about to swallow me. No. this wouldn’t be allowed. And now I was very sure who took it because I’d planted the clue. Sure enough, this time, they didn’t take them all; there were six pills inside.

I called Anna that day and asked her again about the oxycodone. She said she had no idea about any drugs that might be missing. “What about Maria?” I asked. She repeated her denial.

After telling Anna I wouldn’t let this happen again in the future, I once again went through the time-consuming process of requesting 120 more pills for the second time within just two weeks.

The next day, Patrick was discharged from the center. Maria was scheduled to come to help caregive for him a few days later. When she arrived, I spoke with her.

“Oh, no,” she said. “I have no idea what happened to that medicine.”

“But you and your mom are the only people who could come in the house. Nobody else was here,” I insisted. “If you have no idea, do you think your mom did it?”

“Oh, no. No one.” She was laughing about it.

Just before ten o’clock that day, I told her, “Maria, I called the DEA office yesterday. They recommended I should contact local law enforcement to at least investigate what happened.”

Maria gulped but kept the same weird smile on her face she’d worn before.

“Since the situation seems to be out of my control, I’m going to work with the police department on this,” I said firmly. “I don’t know who is responsible, but these are crimes, and until this becomes clear, I won’t be able to have you work for Patrick. I’m sorry, but I’m asking you to resign from this job. But based on our contract, I’ll give you two weeks’ notice from today.”

She was still smiling.

“The officer will be here at noon today,” I told her.

Still, she didn’t lose her half-smile.

Just before eleven, Maria came to me and said, “Kyomi, I’m going to quit.”

“What do you mean?” I asked. “You can stay for two weeks until you find another job.”

“No, I’d rather leave today,” she said with clarity.

“Okay . . . but you’ll stay until 3:00 p.m. today, won’t you?” I asked her.

“No,” she said. “I’m gonna leave now.”

This was the end of our conversation.

The officer came at noon after Maria was gone. I reported the past two incidents. The officer said the opioids’ disappearance must be related to Anna and Maria.

Within a couple of weeks, I completed Maria’s payroll tax and benefits and paid her last salary to close her employment. To my surprise, she then filed for unemployment, and the EDD (Employment Development Department) sent me the unemployment insurance document for me to fill in. I had to deny it; I sent a grievance instead, explaining that she’d resigned from her work despite my offer to let her keep her job for another two weeks. It had been her choice to leave my employment.

I sensed this saga might last much longer than I wished it to.

It turned out that my intuition was right. Until the end of that year, dealing with Maria’s unemployment claims consumed my practical efforts and mental energy. In addition, Anna called me frantically on multiple occasions, accusing and threatening me of having mistreated her daughter. When it was all finally over, I breathed a huge sigh of relief.

Ending thoughts

Maria was only twenty-two years old when all this occurred. Nevertheless, I remember the strange way she smiled when I confronted her, and it still makes me shiver a little.

The opioid crisis has taken its toll. Lots of lives have been lost; perhaps even more relationships have been destroyed. After my limited experience with this crisis, I feel so sorry for the damage these drugs have done. Enticed by the demon’s greed or craving, people’s cognition and personality change, and they lose their connections to love, hope, and humanity. Perhaps these losses are the ones we should grieve the most.

Thank you, Dr. Donna L. Roberts, for your article:

Leave A Comment